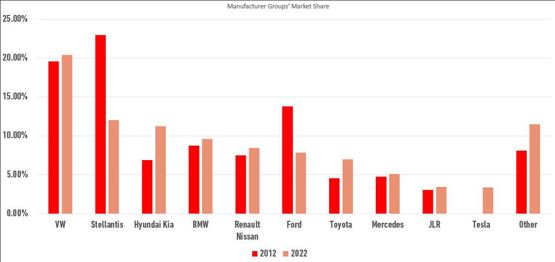

Now the dust is settling on a terrible 2022 (just 1.61 million registrations, the worst figure since 1992), it is worth taking a step back and looking at the market from the point of view of manufacturer groups, rather than individual makes and models.

After all, the health of the parent group is as important (if not more so) than the health of the individual marque, writes David Francis.

To take an extreme example, no dealer is taking on Lotus based on the performance of the Hethel brand over the past 20 years: they are betting that the strength and track record of Geely can create a phoenix out of the ashes.

Looking at the picture over a 10-year period (see chart), there have been some major shifts in the balance of power. The biggest shift has come from Stellantis, whose market share has almost halved. Of course, it should be pointed out that Stellantis did not actually exist in 2012: it is the result of the mergers of PSA Peugeot-Citroën with Opel-Vauxhall (2017) and Fiat Chrysler (2019).

At first glance, Stellantis looks like three drunks leaning against each other for support.

At first glance, Stellantis looks like three drunks leaning against each other for support.

However, Fiat’s takeover of Chrysler after the 2008 financial crash looked much the same, before big profits on US pick-up trucks showed that Fiat’s plan was rather smarter than it first appeared. Hence Stellantis needs a closer examination before coming to conclusions based only on market share.

Making decent money

Certainly, the numbers don’t look good. Whereas the overall car market declined by 20.9%, all the major Stellantis brands fell by between 47% (Peugeot) and 64% (Vauxhall). It was even worse for Alfa Romeo (-78%), and only Maserati increased slightly – but Maserati was supposed to transform from exotic supercar to Porsche-style upper premium brand.

On the plus side, Stellantis reported a record profit margin of 14.1% for the first half of 2022, so it is making decent money on a moderate number of vehicles. To its credit, that is the exact opposite of how Vauxhall, Fiat and Citroën used to do business: they would pump up the volume and sell the unwanted cars for anything they could get.

The big question for Stellantis is just how many brands do they need for Europe? They have four mainstream brands (Citroën, Fiat, Peugeot and Opel-Vauxhall), but also four premium/specialist ones in Alfa Romeo, DS, Jeep and Maserati.

The combined market share of those latter four in 2022 was just 0.53%, or less than Cupra, which is only a couple of years old. Amazingly, there will soon be a fifth premium brand: Lancia is to be reborn in 2024, and could even return to the UK.

Meanwhile, VW maintains its seemingly inexorable progress. Over the same 10 year period, VW, Audi and Škoda have all declined by between 9% and 28%, so very much in line with the overall market. Seat has either fallen by 43% or by 6%, dependent on whether or not you include Cupra – which is effectively “New Seat”.

The group which has grown the fastest is, unsurprisingly, Hyundai-Kia: market share is up from 6.9% in 2012 to 11.3% in 2022. Kia, in particular, surfed the crossover wave brilliantly with the Sportage: when a company’s best-selling model is an aspirational £30k crossover, it is definitely no longer a value brand. What worries the rest of the industry is that Hyundai-Kia could do the same with electric vehicles (EVs). Models such as the Kia EV6 and Hyundai Ioniq 5/Ioniq 6 show they are now front-runners in the EV race.

Terrible product decisions bite

The converse of Hyundai-Kia is Ford. It has fallen from 13.8% to 7.9%, and the situation for Europe as a whole is even worse – just 4.9% market share.

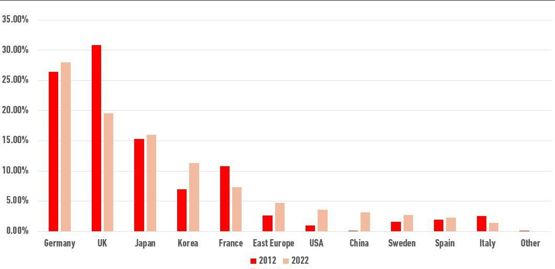

Why does that matter? Ford has stopped manufacturing in emerging markets like Brazil and India, and has also pulled out of small passenger cars in the USA. Its market share does not get close to justifying new platforms for Europe and it has nowhere else to sell hatchbacks.

Why does that matter? Ford has stopped manufacturing in emerging markets like Brazil and India, and has also pulled out of small passenger cars in the USA. Its market share does not get close to justifying new platforms for Europe and it has nowhere else to sell hatchbacks.

While we think of Ford as being a huge player, given its historic market share in the UK, it is actually Europe’s smallest non-premium car manufacturing group. Its future seems to consist of being Europe’s largest van manufacturer plus whatever cars it can adapt from either Ford USA, or competitors in Europe (e.g. using the VW ID3 MEB platform).

From a UK perspective, probably the biggest disappointment is JLR. In 2012, the company was on a roll with the smash-hit Evoque, and the company was soon planning for annual volumes of one million cars per year.

That dream was shattered by terrible product decisions, such as the Jaguar XE that had the same effect on the 3-Series as a peashooter on a tank, the Jaguar XJ that was canned after all the development money had been spent, and the Discovery 5 that was rendered obsolete by the new Defender. Brexit and COVID-19 were contributory problems, but JLR’s biggest issues have been internal, not external.

Tesla upended the premium market

Finally, the biggest worry for all the well-established OEMs are brands that barely existed 10 years ago. Tesla has upended the premium market, although no one knows how far it can go.

Certainly not as far as its bizarre promise of 20 million cars a year, but Tesla has big economies of scale in battery manufacturing that give it a major advantage. Up to now, Elon’s personal image has driven the company’s progress, but the Teflon coating that protects Tesla is under fire like never before. Whether it can remain impermeable is anyone’s guess.

The most serious threat comes from China. In the days of petrol engines, China was a no-hoper – by the time it had learned how to meet one emission standard, the next one was imminent. However, EVs change the calculation completely.

China makes the world’s lowest-cost batteries in the highest volumes. Now that it has learned how to make the rest of a car to a decent standard, it is a deeply worrying competitor.

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.