The UK media and MPs go into overdrive castigating the company, causing sales to collapse in the West Midlands. Registrations that year fall by more than 3,000 units.

Forward to the present, and the company will in December be celebrating its fifth consecutive year of growth (BMW and Mini combined).

It has a young model range, with many critics coming round to the challenging Chris Bangle-inspired design quirks, and there’s more to come next year with the 3-series touring and coupe. Mini is proving to be inspired, prompting plans to extend the model range into four doors and estates.

BMW GB managing director Jim O’Donnell, appointed to the job just after the Rover debacle, is bullish about the future, although he’s aware the business faces a number of challenges from the tough trading environment and the raft of legislative and cost issues affecting its retailer network – some of which he’s prepared to admit are the fault of the carmakers.

He’s concerned that the industry is set for a radical upheaval, one that will mirror the developments in the grocery market where the large national chains replaced the corner shops.

A handful of powerful groups will dominate, with a network of owner-driver rural dealerships, but O’Donnell claims the carmakers will step in if the situation (i.e. balance of power) gets out of hand.

Changing balance of power?

“The bigger dealers will get bigger as the small dealers sell up. The motor trade will get similar to the grocery trade – that’s the potential under Block Exemption,” O’Donnell says.

He illustrates the point by emphasizing the exceptionally high cost of entry to the BMW franchise: £3m for equity and borrowings. But this could cause a problem for carmakers – few want to see the bulk of their networks in the hands of the few; it could shift the balance of power.

Always opinionated, often outspoken, O’Donnell has a reputation for honest, tough talking. And he accepts that carmakers are partly to blame for the problem of consolidating franchised networks.

“We all raised the bar too high on standards, which has seen costs spiral. Then there’s the issue of land and property, and the additional burden of legislation, like health and safety and the FSA,” he says.

BMW’s preferred scenario with its 158-strong network is to stick with its one-third shares between plcs, medium groups and owner-drivers. “And that’s the challenge – keeping a reasonably representative network. But where does the individual go? He sells to the medium group who sells up to the plcs – it’s not long before they get a 50% share of the network. There will be significant changes over the next five years.”

Within the BMW network, O’Donnell predicts a 20% churn during this time, mostly due to the exit of owner-drivers who have already told the carmaker that they intend to retire (the franchise investment plans have a 10-year payback so dealers aged 55 and above do not wish to remain in the business for that long).

He says he would be “disappointed” if he had to sack any dealers, but that the network should be under no illusions that if they don’t perform to expected levels, they will “be encouraged to sell”.

#AM_ART_SPLIT# Wasted time on admin

BMW closely monitors and measures each dealer, and is aware of any shortcomings. And that includes within its own business. “We have wasted dealers’ time on all sorts of things – in particular our administration has not been very good,” O’Donnell says. “The average dealer was receiving more than 500 invoices a month from us, which all had to be checked and processed.

All because no-one asked why. We need to become more efficient, which takes time. Our dealers are trying too, and we are giving them the time to be successful.”

Given the scenario of plcs dominating the BMW network, what are his options? “The only thing that can stop the big getting bigger is a dealer support programme. We have used it, but it’s not a favoured approach. But we would use it if we felt there was a threat to our network.”

O’Donnell has another advantage: five-year fixed contracts. While the majority of the industry went down the two-year rolling contract, BMW (plus Peugeot) went fixed term, with six months’ notice of termination. Those contracts run until October 2008 and will be replaced by another five-year agreement.

“All the big groups want to work with us – and as long as we have that tool in our armoury, we will have a good relationship with dealers,” he says.

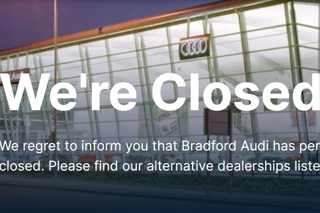

A big issue vexing BMW is the exceptional costs of operating in London (see boxout). In recent months it has seen two dealerships close, operated by HR Owen and Sytner, and O’Donnell expects further rationalisation. BMW currently has 21 franchised sales and aftersales centres within the M25 but he “could see us losing another two or three sites”.

Adjusting expectations

Manufacturers need to adjust their expectations of city centre showrooms. Fleet business, for instance, should be carried out by sites outside the M25, which enables city centre dealers to focus on retail sales, used cars and aftersales. “Those dealers that make it work in London tend to be further out, closer to the M25. The costs are significantly lower, although they are still quite high,” he adds.

Other solutions include carmaker-owned showrooms, subsidising a retailer to do it (“a dangerous precedent”) or doing nothing and lose out on sales (“not an option”).

“Our preference is for our own sites, but we would only start opening them if we started losing our market share in London (currently just over 5%). There’s no evidence that we have lost any sales due to the dealerships that have closed because there is still a choice in London.”

BMW dealers, like every other franchise, have seen profits dip this year, although O’Donnell claims they are still averaging around 1.7% return on sales.

Much of this is due to the high cost of investment in new showrooms to cope with additional volume and the separation of Mini (next year the network will spend £15m on upgrades and new premises). O’Donnell also suspects some retailers have been panic discounting in the fear of missing monthly targets and, therefore, bonuses.

A third issue concerns some managers who have failed to adjust to BMW’s move towards a volume franchise. Since 2000, annual new car sales have doubled, used cars have tripled. It’s turned £20m dealerships into £60m businesses, with implications for management control.

“Our retailers need to be achieving 2.5% returns to sustain investment, customer satisfaction and the best staff,” O’Donnell says. “We expect returns to increase next year with a full year of 3-series and 3-series touring, plus coupe towards the end of the year. The model line up is good; our aspirations for growth are modest.”

Top dealers this year will earn 3% ROS, while 25 outlets are achieving more than £1m profit. They are the ones converting 18% of leads into sales; the worst are around 1% (BMW’s internal targets are 10%). The focus next year is tackling those at the bottom, particularly the 12 or so that are losing money, as the carmaker looks to raise sales from 110,000 this year to 112,000 – around 2% growth.

At one point 110,000 looked unattainable as the company got off to a slow start. O’Donnell says BMW allowed the network to take its “foot off the accelerator” in the first quarter, which he blames on the decision to offer dealers guaranteed bonuses. “That won’t happen again,” he adds.

Mini sales are forecast to drop 10% next year due to production capacity, which will dishearten those retailers currently investing millions in standalone showrooms. It will, however, be a short-term blip, and one that is sure to preserve residual values.

O’Donnell says it will also help to encourage dealers into used cars and offers them a chance “to take a breath” after rapid growth. “Next year is an opportunity for our dealers to raise profits per units because our sales growth ambitions are modest,” he says. “With our next models they should make their targets without the need for discounting, which will raise profit per unit.”

BMW, like all carmakers, needs a retail network that is making money in order for reinvestment in premises, training and customer service.

And, while slightly in jest, O’Donnell offers another view why he needs profitable dealers: “The more money dealers make, the higher they’ll jump when you say ‘jump’.”

BMW sales tracker:

The blip in 2000 coincided with BMW selling Rover – that decision promoted angry protests and falling, particularly in the West Midlands. It was only short-term, however.

#AM_ART_SPLIT# London justifies higher rates

Congestion charging is a pet hate for Jim O’Donnell. For the past three years he has vented his spleen about Ken Livingstone’s London legacy at the annual press dinner.

It will cost, he says, BMW’s Park Lane dealer £200,000 this year, and £300,000 next year when charges increase. And that’s not all: £700,000 is put aside to cover parking charges, and then there’s collection and delivery and courtesy cars.

“It’s no wonder dealers have to charge £100-plus per hour for servicing rates,” says O’Donnell. “That’s got nothing to do with ‘rip-off Britain’ as some tabloids suggest.”

The BMW/Mini dealership turns over £110m combined, but makes just £1m profit. Five years ago it would’ve made £5m on this level of turnover. But there’s no question of pulling out –BMW needs the representation.

O’Donnell adds: “Independent retailers in London will cease to exist by the time of the 2010 Olympics.”

Analyst's view: Prestige with volume sales

BMW’s success is down to a combination of strong product and demand greater than supply, according to one analyst, who wished to remain anonymous.

“These factors make BMW very profitable, compared to other brands. It’s one thing to be in demand but it’s another to have a few orders under your sleeve.

The company has not had to offer incentives to attract buyers but has still managed to increase sales,” he says.

“The move into niche models has also helped, especially considering the brand was traditionally based on a saloon range and models like the X5 and the 1-series have boosted sales considerably. The secret has been to shift volume while still maintaining its status as a premium brand.

“In terms of dealers it’s a bit chicken and egg. BMW is a desirable brand to have but it is legendary how tough they are with dealers. However, for those that put a lot into it the returns are very good.”

Login to comment

Comments

No comments have been made yet.