By Philip Nothard, CAP retail and consumer price editor

Car colour is one of the perennial topics of conversation in our industry. For motorists it ranks right up there as one of the critical factors in their purchase choices and therefore, for dealers, it is necessarily a consideration when choosing stock.

Every piece of research confirms the bottom line – that you can always charge more for one colour than another. When we asked dealers whether they could charge more for the right colour, 92% agreed outright that they could.

The remainder suggested it may be more a case of having to charge less for those colours that are more rarely sought. But the fact is that colour is money. It was also clear that perceptions of colour are highly subjective and that not everyone agrees on the best and the worst colours.

No one will be surprised at claims that white is now the most popular colour for new cars. Only last year, paint manufacturer DuPont confirmed it in their Automotive Popularity report, which saw white pushing black into second place.

The demise of once-ubiquitous silver has also been well documented, but what might surprise some is that brown or beige was as well-liked by consumers as red. Yet how many dealers would baulk at putting a brown or beige car on the forecourt, while having no problem with a red car?

In the used market this becomes interesting due to the inevitable lag between the new car trend and what is actually available as used car stock.

Some insight into this is provided by analysis from Driving.co.uk showing uploaded dealer stock profile by colour and age. Limiting the data to five years or younger and between the dates of March and June this year, black remains the most popular, accounting for more than 25% of total stock uploaded by dealers for sale. But white is beginning to catch up as five years of new car popularity gradually enters the used market so that – over the period – white cars have grown from just 2.26% of stock at five years to more than 20% of stock at less than a year old.

But we should not forget that colour ‘popularity’ is really driven in the first instance by manufacturer decisions around their new car offering. Does this therefore mean that the relative proportions of colour choice translate happily into the used market? Or do dealers have difficulty getting the balance right on the used car forecourt?

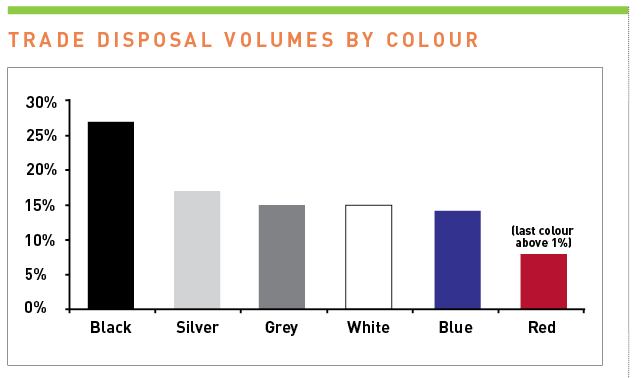

Analysis of trade data over the previous six months reveals that white is in joint third place with grey and still behind silver .

What is interesting is how many contrasting views are revealed when you speak to key players around the industry. For example, Manheim’s head of marketing, Andy Cullwick, argues that while colour is one of the emotional drivers for a consumer, it is important to remember that tastes change. As he suggests, today’s white could become tomorrow’s black, grey or even green or beige.

Meanwhile, BCA revealed that analysis of more than 40,000 trade vehicles showed a different picture than the Motors data, with silver cars leading the pack on 29.5% of the total, ahead of black on 25%. The supposedly unpopular blue accounted for 20%, with grey in fourth place with 13%. They told us that, of the more popular colours, white cars achieved the highest value on average, while grey and black cars outperformed other colours in terms of price. But they were careful to point out that white cars were sold at a younger age (37 months) and lower mileage (43,000) than the sample average of 60 months and 58,000 miles.

Our own research among dealers suggests that many hope white does not maintain its current supremacy because they resent price discrepancies amounting to as much as £1,000 in some cases. Much depends on whether the premium in the trade can be passed on to the consumer. And this often depends on a deep market knowledge such as when is the right time to buy a yellow Ford Focus? Because this car will command a typical retail premium of more than £700. And stepping outside the run of the mill colours to buy a Liquid Yellow Clio RS means being able to charge something in the region of £1,300 extra to the motorist. But, of course, if it commands a similar premium in the trade market then there is no real advantage.

Philip Nothard - 06/08/2013 12:15

.